Stiff Person Spectrum Disorder

Clinical Overview

Stiff Person Syndrome (SPS) is a rare autoimmune movement disorder that affects central nervous system and is clinically characterized by muscle stiffness, spasms and increased startle response (unconscious defensive response) to unexpected stimuli.

SPS belongs to the group of Stiff person syndrome spectrum disorders (SPSD) that share the same clinical features and spectrum of antibodies against neuronal proteins, that participate in normal inhibition of central hyperexcitability which explains its clinical characteristics. The exact pathophysiological mechanism is still not known.

Muscle stiffness usually begins insidously in lower back and legs and can mimic lower back pain, but in time tends to progress to other body parts, mainly to distal limb parts and abdominal muscles. As a result patients present with typical “stiff” or “robotic” gait with exaggerated lumbar hyperlordosis. Stiffness usually resolves in sleep or under anesthesia.

View complete description

Muscle spasms in SPS are painful and intermittent. They typically occur as a result of unexpected external stimuli, mainly to tactile, acoustic or emotional stimulus and usually last for few seconds or minutes. Extreme spasms can lead to spontaneous fractures and joint subluxations or uncontrolled falls of the person with typical “log-like” falling down.

Patients with SPS also often manifest non-motor features such as anxiety, depression and task specific phobias. The most common is agoraphobia, with fear of falling down if walking unaided. Also, there can be transient symptoms of autonomic dysfunction leading to sympathetic hyperactivity with diaphoresis, hyperpyrexia or sexual dysfunctions.

Besides classical SPS there are focal forms of disease when symptoms are isolated on one body part, e.g. Stiff limb syndrome, or forms associated with additional neurological features (e.g. epilepsy, ataxia, polyneuropathy) and also fulminant and sometimes fatal forms such as Progressive encephalomyelopathy with rigidity and myoclonus (PERM).

Diagnosis of SPS is based on its clinical presentation. Findings of elevated standard antibodies titres against GAD, glycine, DPPX, GABARAP, gephyrin and ampiphysine in cerebrospinal fluid and blood may be helpful but are not crucial for the diagnosis. EMG studies show unspecific continuous motor unit activity potentials (CMAP) in affected muscles. Electrophysiological studies of exteroceptive reflexes with abnormal masseter inhibitory reflex with loss of S2 component, and shortened latency of R2 recovery in Blink reflex are more specific.

Brain and spine MRI are normal and are used only to exclude other possible diagnoses.

SPS is commonly associated with other autoimmune diseases, including vitiligo, diabetes mellitus and thyroiditis. Some forms (mainly associated with anti-ampiphysin antibodies) may be associated with neoplasms.

The therapy of SPSD is based on the triad of symptomatic treatment, immunotherapy, and tumor removal/oncological treatment where appropriate.

Symptomatic treatment is based on drugs with GABA-ergic action. Nevertheless, due to its autoimmune nature, the core treatment is immunotherapy utilizing corticosteroids, intravenous immunoglobulins (IVIG) and/or plasma exchange as first line therapy, escalated to second line immunotherapy utilizing e.g. cyklosporin, cyklofosfamid or mycofenolat mofetil in unresponsive cases. Treatment of the underlying oncological process is crucial in cases with paraneoplastic association.

The prognosis of the disease is variable.

Contributed by Kailash Bhatia, MD

Institute of Neurology

Sobell Department

London, UK

2019 Updates Contributed by:

Petra Dosekova, MD

Movement Disorders Unit and Center for Rare Movement Disorders,

Dept. of Neurology

P. J. Safarik University

Kosice, Slovakia

Latest Content

![]()

Hot topics and controversies on Stiff Person Spectrum Disorders (SPSD)

- Web article

- Functional Movement Disorders

- Stiff Person Syndrome (SPS)

Related Courses

Informational Materials

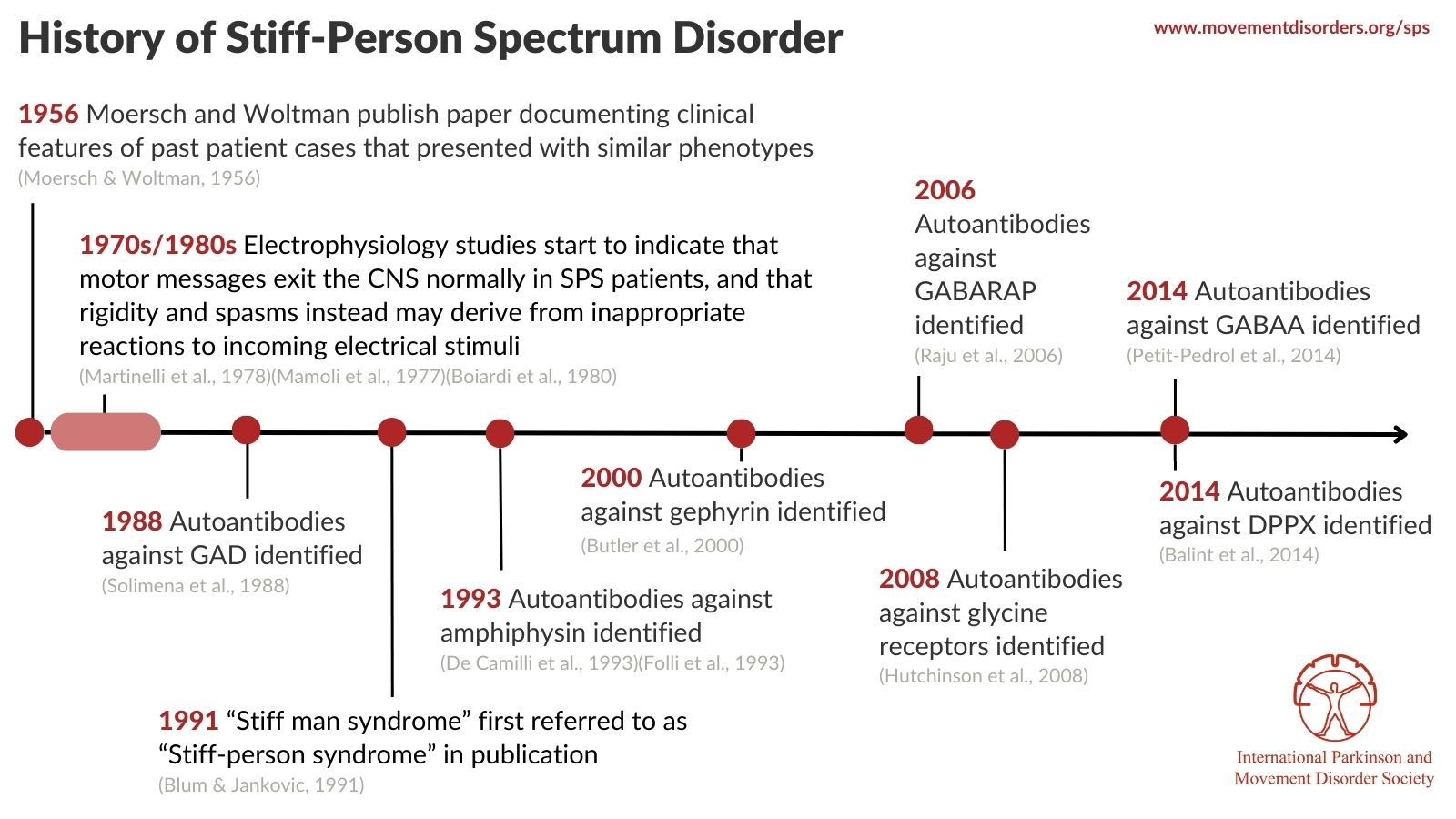

Timeline of SPS History

View references

REFERENCES

Balint, B., Jarius, S., Nagel, S., Haberkorn, U., Probst, C., Blöcker, I. M., Bahtz, R., Komorowski, L., Stöcker, W., Kastrup, A., Kuthe, M., & Meinck, H. M. (2014). Progressive encephalomyelitis with rigidity and myoclonus: a new variant with DPPX antibodies. Neurology, 82(17), 1521–1528. https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0000000000000372

Blum, P., & Jankovic, J. (1991). Stiff-person syndrome: an autoimmune disease. Movement disorders : official journal of the Movement Disorder Society, 6(1), 12–20. https://doi.org/10.1002/mds.870060104

Boiardi, A., Crenna, P., Bussone, G., Negri, S., & Merati, B. (1980). Neurological and pharmacological evaluation of a case of stiff-man syndrome. Journal of neurology, 223(2), 127–133. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00313175

Butler MH, Hayashi A, Ohkoshi N, et al. Autoimmunity to gephyrin in Stiff-Man syndrome. Neuron. 2000;26(2):307-312. https://doi:10.1016/s0896-6273(00)81165-4

Blum, P., & Jankovic, J. (1991). Stiff-person syndrome: an autoimmune disease. Movement disorders : official journal of the Movement Disorder Society, 6(1), 12–20. https://doi.org/10.1002/mds.870060104

De Camilli P, Thomas A, Cofiell R, et al. The synaptic vesicle-associated protein amphiphysin is the 128-kD autoantigen of Stiff-Man syndrome with breast cancer. J Exp Med. 1993;178(6):2219-2223. https://doi:10.1084/jem.178.6.2219

Folli F, Solimena M, Cofiell R, et al. Autoantibodies to a 128-kd synaptic protein in three women with the stiff-man syndrome and breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 1993;328(8):546-551. https://doi:10.1056/NEJM199302253280805

Hutchinson M, Waters P, McHugh J, et al. Progressive encephalomyelitis, rigidity, and myoclonus: a novel glycine receptor antibody. Neurology. 2008;71(16):1291-1292. https://doi:10.1212/01.wnl.0000327606.50322.f0

Martinelli, P., Pazzaglia, P., Montagna, P., Coccagna, G., Rizzuto, N., Simonati, S., & Lugaresi, E. (1978). Stiff-man syndrome associated with nocturnal myoclonus and epilepsy. Journal of neurology, neurosurgery, and psychiatry, 41(5), 458–462. https://doi.org/10.1136/jnnp.41.5.458

Meinck, H. M., Ricker, K., & Conrad, B. (1984). The stiff-man syndrome: new pathophysiological aspects from abnormal exteroceptive reflexes and the response to clomipramine, clonidine, and tizanidine. Journal of neurology, neurosurgery, and psychiatry, 47(3), 280–287. https://doi.org/10.1136/jnnp.47.3.280

Moersch FP, Woltman HW. Progressive fluctuating muscular rigidity and spasm ("stiff-man" syndrome); report of a case and some observations in 13 other cases. Proc Staff Meet Mayo Clin. 1956;31(15):421-427.

Mamoli, B., Heiss, W. D., Maida, E., & Podreka, I. (1977). Electrophysiological studies on the "stiff-man" syndrome. Journal of neurology, 217(2), 111–121. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00312924

Petit-Pedrol M, Armangue T, Peng X, et al. Encephalitis with refractory seizures, status epilepticus, and antibodies to the GABAA receptor: a case series, characterisation of the antigen, and analysis of the effects of antibodies. Lancet Neurol. 2014;13(3):276-286. doi:10.1016/S1474-4422(13)70299-0

Raju R, Rakocevic G, Chen Z, et al. Autoimmunity to GABAA-receptor-associated protein in stiff-person syndrome. Brain. 2006;129(Pt 12):3270-3276. https://doi:10.1093/brain/awl245

Solimena M, Folli F, Denis-Donini S, et al. Autoantibodies to glutamic acid decarboxylase in a patient with stiff-man syndrome, epilepsy, and type I diabetes mellitus. N Engl J Med. 1988;318(16):1012-1020. https://doi:10.1056/NEJM198804213181602

SPS Social Media Graphics

About SPS