VOLUME 29, ISSUE 2 • JUNE 2025. Full issue »

VOLUME 29, ISSUE 2 • JUNE 2025. Full issue »

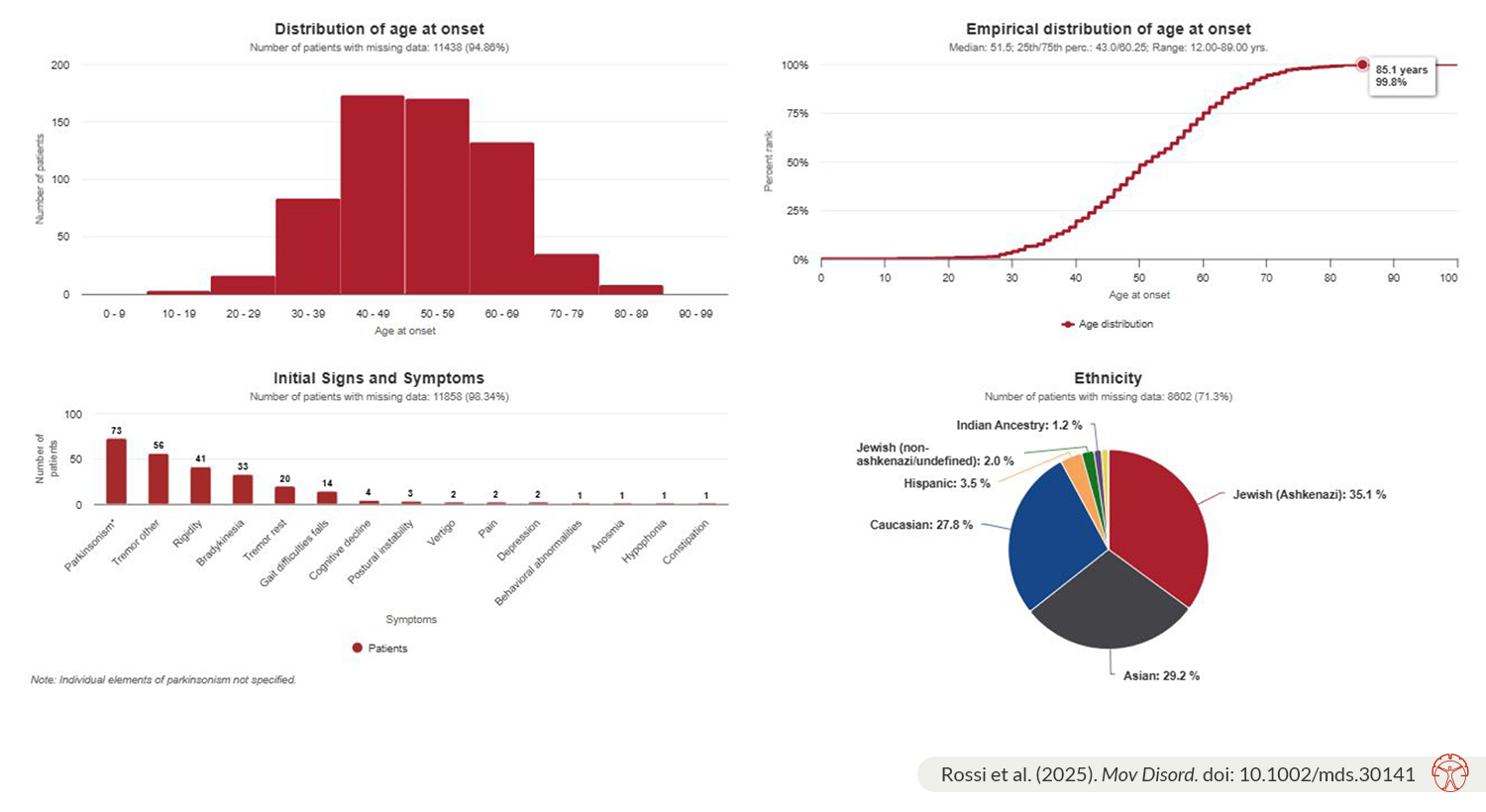

Our recent MDSGene Systematic Review on the classification and genotype-phenotype relationships of GBA1 variants covers 27,963 patients carrying GBA1 variants from 1,082 publications with 794 variants, including 13,342 patients with Parkinson’s disease (PD) or other forms of parkinsonism. It provides a comprehensive overview of demographic, clinical, and genetic findings from an ethnically diverse sample originating from 82 countries across five continents. Additionally, the report of almost 800 GBA1 variants highlights how quickly the list of GBA1 variants has expanded over the past three decades, since the early association of Gaucher's disease (GD) and a few GBA1 variants with PD.

The major highlights for why there was a need for this review are as follows: |

|

These factors highlight the importance of the review in advancing knowledge and guiding future research and clinical practices.

The salient findings of the study include: |

|

The major gap identified in reviewing the existing literature is a high proportion of missing data due to insufficiently detailed patient descriptions in the included publications, as noted in other MDSGene systematic reviews. A concerning observation is the underreporting of many demographic and clinical features, such as age at disease onset, ethnicity, the four cardinal motor features of PD, and several non-motor symptoms. To overcome these gaps and improve the quality of evidence, it is essential to encourage the inclusion of more demographic and clinical information in study population descriptions, as well as the publication of case reports and series to better assess genotype-phenotype relationships of different GBA1 variants. This would aid in the selection and stratification of patients for ongoing and future clinical trials. This also serves as a call to action for the development of a standardized reporting tool to ensure the quality and completeness of clinical feature descriptions for patients with movement disorders and to accurately report the frequency of PD's cardinal motor and non-motor features, thus preventing the high rate of missing clinical data seen in many publications.

With this review, we start to fill the gaps regarding genotype-phenotype correlations in GBA1 variant carriers, especially concerning PD. This review can be used to identify specific variants according to pathogenicity and as an overview of the phenotypes of different variants. For this, different filter options, such as for certain demographic or clinical variables or genetic variants, are available on the MDSGene website (www.mdsgene.org).

References

1. Rossi M, Schaake S, Tatiana Usnich, Josephine Boehm, Nina Steffen, Nathalie Schell, Clara Krüger, Tuğçe Gül-Demirkale, Natascha Bahr, Teresa Kleinz, Harutyun Madoev, Björn-Hergen Laabs, Ziv Gan-Or, Roy Alcalay, Katja Lohmann, Christine Klein. Classification and Genotype-Phenotype Relationships of GBA1 Variants: MDSGene Systematic Review. Mov Disord. 2025 Feb 10. doi: 10.1002/mds.30141. Online ahead of print.

Read more Moving Along: